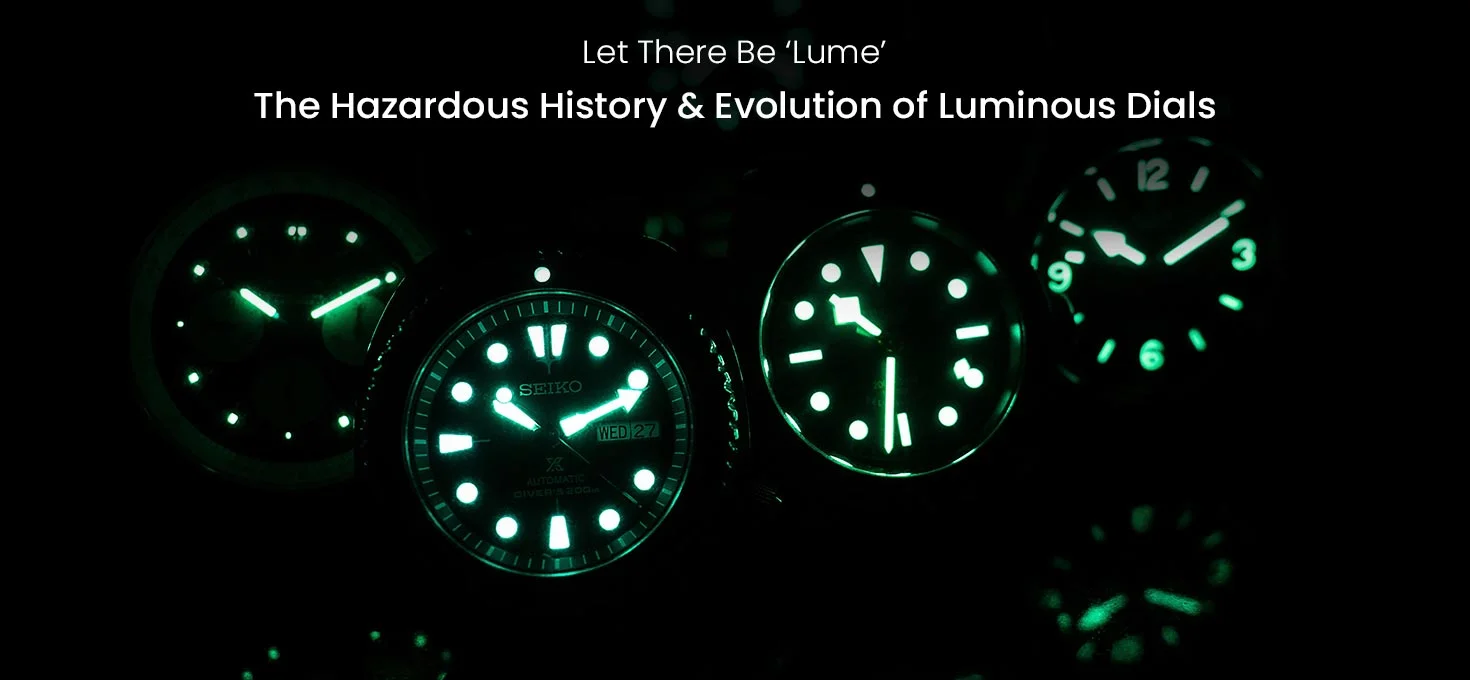

If you’re wearing a timepiece while spelunking into dark, treacherous caves or exploring ocean beds void of sunlight, chances are, your timepiece is emitting a ‘luminous’ glow – thanks to a special ingredient. This luminous material on watch dials, shorthanded as “lume”, is one of watchmaking’s most fascinating avenues as it bridges the gap between visibility and functionality. In this modern era, lume is a staple on every watch intended for diving, adventure, or tactical use – the only exemptions are those that bear sonneries, minute repeaters or are designated for ballroom affairs.

The history of lume, its various magic ingredients, and the science behind its luminosity is a tale of innovation as much of caution. Here’s everything you need to know about “lume” and luminous watch dials.

First Signs Of ‘Lume’

As we’re nearing the dawn of the 20th Century, innovation and exploration were rampant, and timepieces needed dials that could be worn beyond the hours of daylight. During this time, Polish French chemists Maria Skłodowska and Pierre Curie discovered ‘Radium’ paint – a luminescent paint comprising radium and zinc sulfide. From cosmetics and aviation to ammunition equipment and quack medical treatments, this sparked a multi-industrial obsession with this ingredient until it found military use in WW1. Scientists discovered that the effect of radium could be amplified through the process of electrolysis – a particularly essential trait that could provide legibility for soldiers observing pocket watches in dark battlefield trenches.

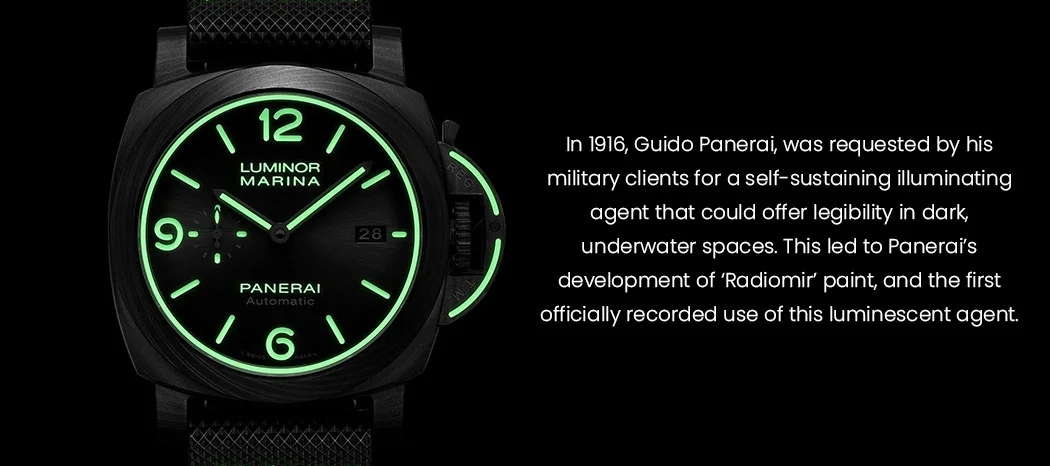

In 1916, Guido Panerai, a Florentine retailer, was requested by his military clients for a self-sustaining illuminating agent that could offer legibility in dark, underwater spaces. This led to Panerai’s development of ‘Radiomir’ paint, and the first officially recorded use of this luminescent agent was on diving watches and precision instruments for the Italian Navy. This consisted of radium bromide, zinc sulfide and mesothorium and was applied to the dials of first-gen military-commissioned Panerai watches.

The Luminous Hazards of Innovation

By the Art Deco era, the world was spellbound by the illuminating glow of Radium paint, as it was aggressively marketed across industries as an ‘elixir of tomorrow’. Rampantly used in cosmetics, young women applied facial creams and lip paint, which carried highly diluted forms of radium – hazardous, yet not fatal. During this time, radium was also medically advertised as a miracle cure for skin cancer and other dermatological diseases. However, its mesmerising glow blinded the people to its hazardous, true scientific nature.

Radium, as the name implies, is radioactive, with a half-life of 1,600 years, and its fatality was brought to light by the ‘Radium Girls’ of the 1920s. These were female factory workers assigned to paint watch dials with radium paint. During their shifts, they developed a habit of licking the bristles of their paint brushes to ensure a tine tip while painting, resulting in them ingesting the radium paint. This ludicrously hazardous practice caused the female workers to fall ill and suffer from necrosis of the jaw, bone cancer, and even death. In the 1920s, these ‘Radium Girls’ successfully sued the United States Radium Corporation in New Jersey, establishing a precedent for strict labour laws – eventually leading to the complete abandonment of radium as a luminous agent in the 1960s.

New World, New Lume: Tritium & Promethium

As the hazardous glow of radium faded into history and the watchmakers were set free after WW2, the quest for a safer alternative ushered in a new era of luminescence. Promethium and Tritium emerged as leading agents that offered radiance without the perilous shadows of radioactivity.

Promethium was watchmaking’s ‘quick fix’ as a radium alternative. It had a half-life of only two-and-a-half years, considerably safer than radium but also significantly less luminous. Its brightness was undeniable but fleeting. While its employment was short, it marked the beginning of non-radioactive luminous breakthroughs. What followed wasn’t perfect either, but it fixed the endurance issue. Tritium, a delicate isotope of hydrogen, came encased in minuscule glass capsules known as gaseous tritium light sources (GTLS) in the ‘90s, boasting a decent half-life of 12.3 years as a low-energy beta emitter. Its glow was steady, dependable, and far less hazardous than radium. Apart from this, it was self-sustaining and didn’t require external light to “charge up”. These were typically placed in key parts of a timepiece’s dial, like indexes, or directly under the crystal for maximum luminosity and legibility. Unfortunately, tritium tubes and dial paint tended to leak onto a wearer’s skin, and despite being used by numerous watch brands, it was banned in 1998.

Enter, LumiNova & Super-LumiNova

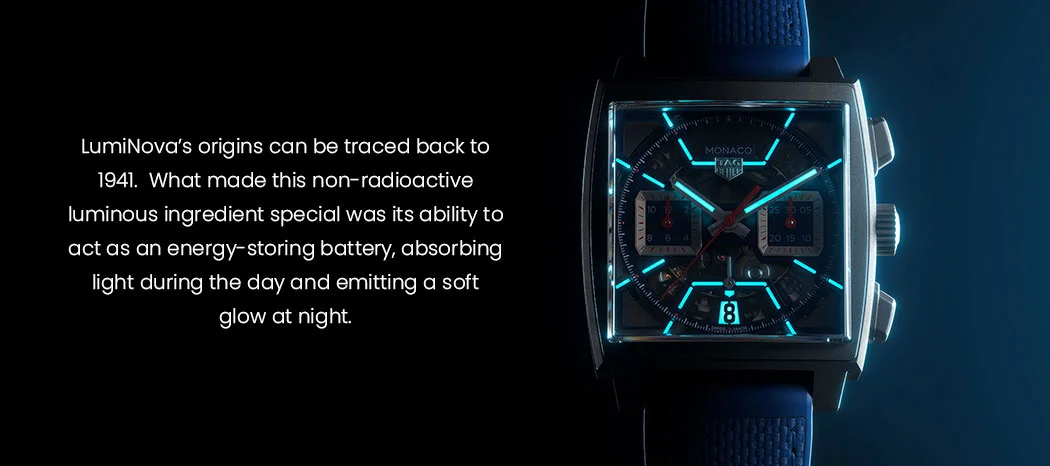

LumiNova’s origins can be traced back to 1941, which interestingly predates its predecessor’s involvement in watchmaking. The Japanese military contracted Japanese inventor Kenzo Nemoto to develop a luminous paint for the cockpit gauges of military aircraft. It needed to be phosphorescent, non-radioactive, and capable of multi-application. As WW2 ended, Nemoto turned his attention to watch dials and officially developed LumiNova in 1993. What made this luminous ingredient special was its ability to act as an energy-storing battery, absorbing light during the day and emitting a soft glow at night. He then licenced the patent for this magic ingredient to the Swiss firm RC Tritec AG, who then renamed it Super-LumiNova. To date, they’re the only official manufacturer of Super-LumiNova in Switzerland. Based on strontium aluminate, it must be activated and isn’t phosphorescent.

Undying Spirit of Experimentalism

Super-LumiNova is revered as the gold standard in the luxury watch industry today. It typically graces the hour, minute, and seconds hands and/or the hour indexes. While this started with a green luminescent hue, Super-LumiNova’s applications have innovated and explored the colour spectrum with blue, orange, pink, and violet tones. Watchmakers have gone further, dipping entire dials in Super-LumiNova like TAG Heuer’s Aquaracer Professional ‘Night Diver’. However, the epitome of lume innovation is IWC’s Ceralume Pilot’s Watch 41, which debuted mid-2024. IWC’s experimental engineering division, XPL, developed a revolutionary case manufacturing process of mixing ceramic powder with Super-LumiNova pigments. As the strap received the same treatment, it created the world’s first ‘fully luminous’ watch.

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

Archives